བཙན་བྱོལ་བོད་གཞུང་གི་རྒྱལ་རྟགས།

- རྒྱལ་རྟགས་ཀྱི་གཞི་ལྗོངས་གངས་རི་གསུམ་གྱིས་མདོ་དབུས་ཁམས་གསུམ་སྟེ་གངས་ལྗོངས་བོད་ཆོལ་ཁ་གསུམ་མཚོན།

- གངས་ལྗོངས་ཀྱི་སེང་གེ་གཡུ་རལ་ཅན་ཕོ་མོ་གཉིས་ཀྱིས་གསེར་གྱི་འཁོར་ལོ་རྩིབས་བརྒྱད་མཉམ་འདེགས་བྱེད་པས། དམ་པའི་ཆོས་ཀྱི་ལྟ་བ་གཞི་རྩར་བྱས་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་ཀྱིས་བོད་ལྗོངས་མཐའ་དབུས་ཀུན་ཏུ་ཉེ་རིང་མེད་པར་སྐྱོང་བ་མཚོན།

- གསེར་གྱི་འཁོར་ལོའི་ལྟེ་བར་ནོར་བུ་དགའ་འཁྱིལ་ཁ་དོག་གསུམ་ལྡན་གཡས་སུ་འཁོར་བས། བོད་འབངས་རྣམས་ལྷག་པའི་ལྷ་སྤྱན་རས་གཟིགས་དང་། འཇམ་པའི་དབྱངས། ཕྱག་ན་རྡོ་རྗེ་བཅས་ལ་དད་ཅིང་། དེ་དག་གིས་རྗེས་སུ་བཟུང་བ་མཚོན།

- རྒྱལ་རྟགས་ཀྱི་གཞི་ལྗོངས་གངས་རི་གསུམ་གྱིས་མདོ་དབུས་ཁམས་གསུམ་སྟེ་གངས་ལྗོངས་བོད་ཆོལ་ཁ་གསུམ་མཚོན།

- ནམ་མཁའ་གཡའ་དག་པར་ཉི་ཟླ་གཉིས་དུས་གཅིག་ཏུ་འཆར་བས། བོད་འབངས་ཡོངས་རྫོགས་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་མདུན་སར་འདྲ་མཉམ་དང། སྐྱེ་བོའི་རྒྱུད་ཀྱི་རྨོངས་པ་སེལ་བ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་སྐྱེ་འགྲོ་ཐམས་ཅད་རྟག་ཏུ་ཞི་བདེར་རོལ་བ་མཚོན།

- མཐའ་མུ་འཁྱུད་སེར་པོས་བསྐོར་བས་བོད་འབངས་རྣམས་ཁོར་ཡུག་གཅིག་གི་ནང་དུ་ཆིག་སྒྲིལ་དུ་གནས་པའི་མཚོན་རྟགས་བཅས་སོ།

- མཐུན་འགྱུར་གནང་མཁན་བཀའ་དྲུང་ཡིག་ཚང་།

National Emblem of the Tibetan Government-in-Exile

- Three snow mountains symbolize three cholka (or provinces) of Tibet; U-Tsang, Kham and Amdo.

- Two snow lions holding an eight-spoked dharma-wheel represent the rule of law according to the principles of Buddhism.

- The multi-coloured swirling gemstone at the centre of the dharma-wheel stands for the Tibetan Buddhist Bodhisattvas, Manjushri, Avalokiteshvara and Vajrapani.

- The sun and the moon in the blue sky mean that every citizen is equal before the law, leading to enlightened minds of the people and peaceful co-existence of all on Tibet’s soil.

- The yellow border symbolises the unity of the Tibetan people.

200 years ago, everyone lacked democratic rights. Now, billions of people have them

Which political systems does the ‘Regimes of the World’ classification distinguish?

In closed autocracies, citizens do not have the right to choose either the chief executive of the government or the legislature through multi-party elections.

In electoral autocracies, citizens have the right to choose the chief executive and the legislature through multi-party elections; but they lack some freedoms, such as the freedoms of association or expression, that make the elections meaningful, free, and fair.

In electoral democracies, citizens have the right to participate in meaningful, free and fair, and multi-party elections.

In liberal democracies, citizens have further individual and minority rights, are equal before the law, and the actions of the executive are constrained by the legislative and the courts.

When French revolutionaries stormed the Bastille prison in 1789 in pursuit of liberty, equality, and fraternity (and weapons), they could not have imagined how far democratic political rights would have spread a mere 200 years later. In the 19th century, there were few countries one could call democracies. Today, the majority are.

བོད་མིའི་མང་གཙོའི་ཀ་བ་གསུམ།

ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༡༩༩༡ ལོར་བཙན་བྱོལ་བོད་མིའི་བཅའ་ཁྲིམས་གཏན་ལ་ཕབ་པའི་མང་གཙོའི་ཀ་བ་གསུམ་ནི། ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་དབང་འཛིན་པཿ ཆེས་མཐོའི་ཁྲིམས་ཞིབ་ཁང་དང་། ཁྲིམས་བཟོ་ལྷན་ཚོགསཿ བོད་མི་མང་སྤྱི་འཐུས་ལྷན་ཚོགས། ལག་བསྟར་འཛིན་སྐྱོང་པཿ བཀའ་ཤག་བཅས་ཡིན།

The Three Pillars of Tibetan Democracy

In 1991, the Charter of the Tibetans-in-Exile established the three pillars of Tibetan democratic governance: the Judiciary (Supreme Justice Commission), Legislature (Parliament), and Executive (Kashag).

Executive

The Kashag (Cabinet) is the highest executive office of the Central Tibetan Administration.

Virtual TourJudiciary

The Tibetan Supreme Justice Commission is the highest judicial organ and one of the three most important pillars of the CTA.

Virtual TourLegislative

The Tibetan Parliament in Exile (TPiE) is the unicameral and highest legislative organ of the Central Tibetan Administration.

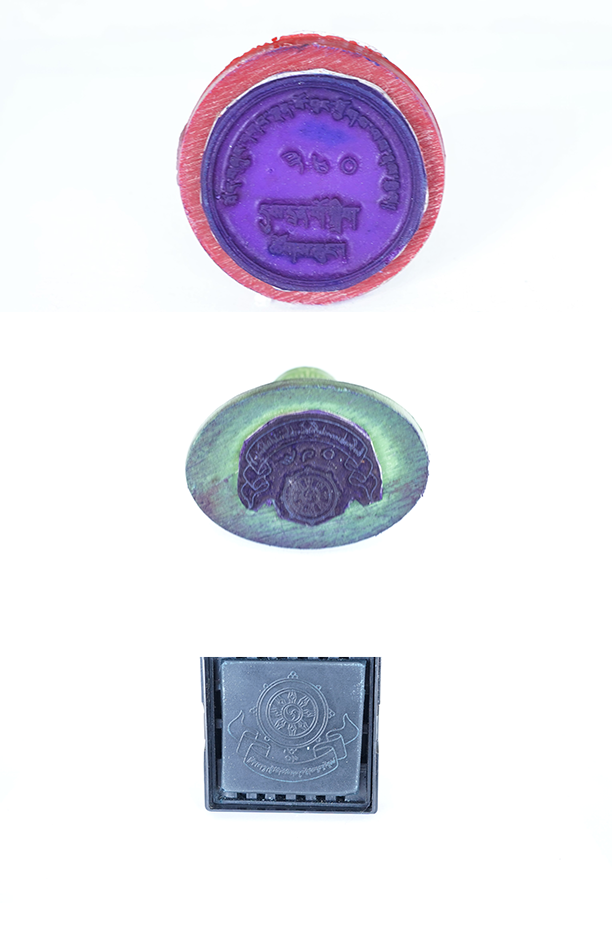

Virtual Tourའདི་དག་དེ་སྔ་༸གོང་ས་མཆོག་གིས་བཙན་བྱོལ་བོད་མིས་འོས་འདེམས་བྱས་པའི་དབུ་ཁྲིད་ལ་ཕྱི་ལོ་༢༠༡༡ལོར་ཆབ་སྲིད་ཀྱི་སྐུ་དབང་རྩིས་སྤྲོད་མ་གནང་གོང་གི་བཀའ་ཤག་གི་ཐམ་ཀ་རྣམས་རེད།

These are stamps from the Kashag, the highest executive body of the Central Tibetan Administration. The stamps were made prior to the devolution of the Dalai Lama’s political power to an elected leader in 2011. The imprints bear the name of the Ganden Phodrang.

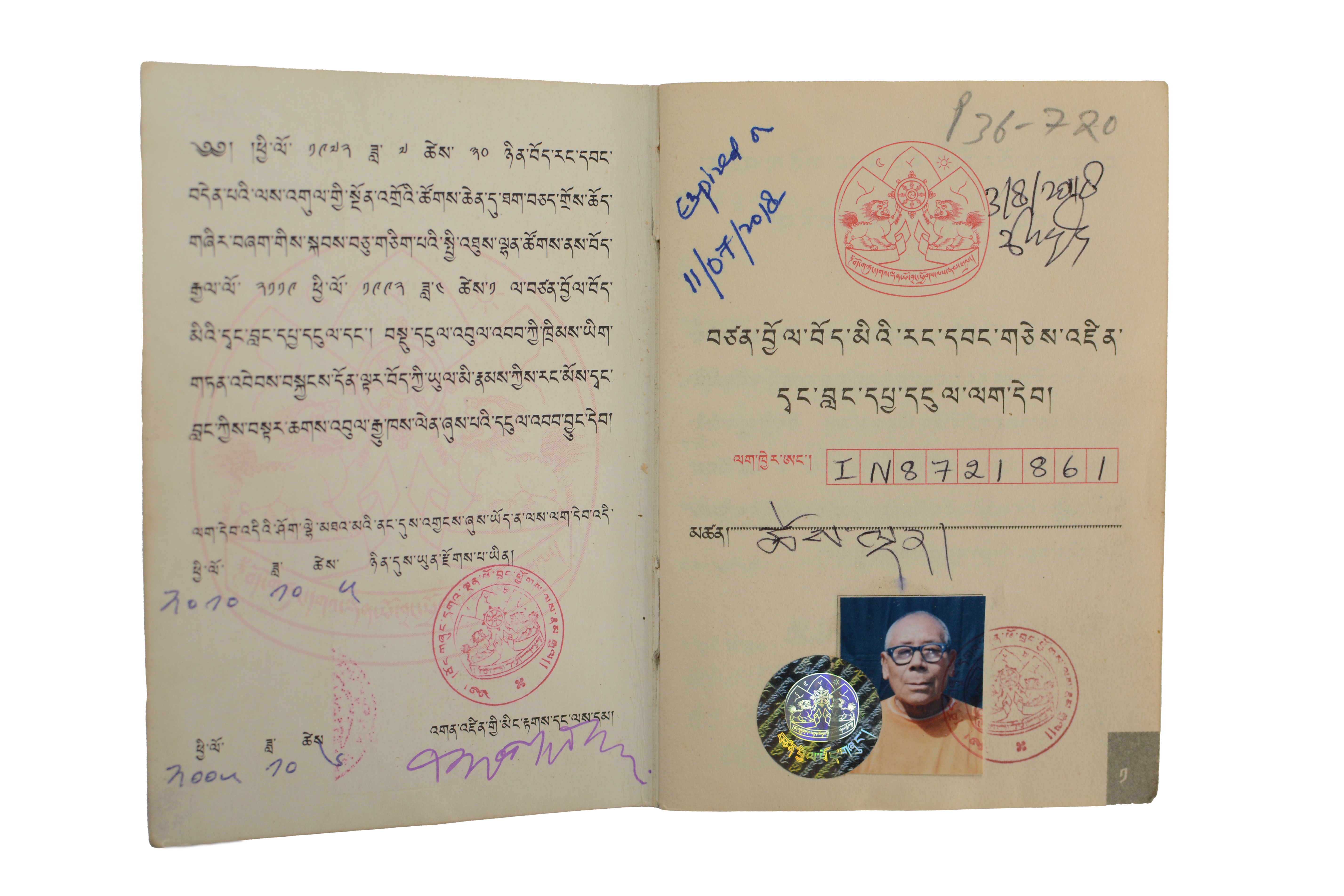

ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༡༩༧༢ ཟླ་བ་ ༨ པའི་ཚེས་ ༡༥ ཉིན་གསལ་བའི་དཔྱ་ཁྲལ་ལག་དེབ།

ལག་དེབ་འདིར་བོད་མི་བཙན་བྱོལ་བ་མི་རེ་ངོ་རེས་བོད་མིའི་སྒྲིག་འཛུགས་ལ་ལོ་རེའི་དང་བླངས་དཔྱ་ཁྲལ་འབུལ་འབབ་ཞིབ་ཕྲ་གསལ་གྱི་ཡོད་ལ། བྱིས་པ་ལོ་དྲུག་ཡན་གྱིས་འབུལ་དགོས་ཀྱི་ཡོད། བོད་མི་བཙན་བྱོལ་བའི་སློབ་གྲྭར་གསར་འཇུག་དང་། སློབ་གྲྭའམ་མཐོ་སློབ་ཁག་ཏུ་སློབ་ཡོན་ཞུ་ལེན། བཙན་བྱོལ་བོད་མིའི་སྤྱི་ཚོགས་སྒྲིག་ཁོངས་ལས་བྱེད་དུ་གསར་ཞུགས། དེ་བཞིན་སྲིད་སྐྱོང་དང་སྤྱི་འཐུས་འོས་འདེམས་ཆེད་ངེས་པར་མཁོ་བ་སོགས་སྤྱི་སྒེར་ཐོབ་ཐང་དུ་མར་འབྲེལ་བའི་ངོ་སྤྲོད་ལག་དེབ་ཅིག་ཡིན།

Chatrel or the Tibetan Green Book 15 August 1972

This is a receipt book that details annual voluntary contributions made by Tibetans-in-Exile to the Central Tibetan Administration. Every Tibetan over the age of six is asked to make a contribution. This book has become our ‘passport’ allowing us to claim our rights from the CTA. Today, it is used to gain school admission, school or university scholarships, and employment within the exiled community. A Tibetan must also have a Green Book if they want to vote in parliamentary and President elections.

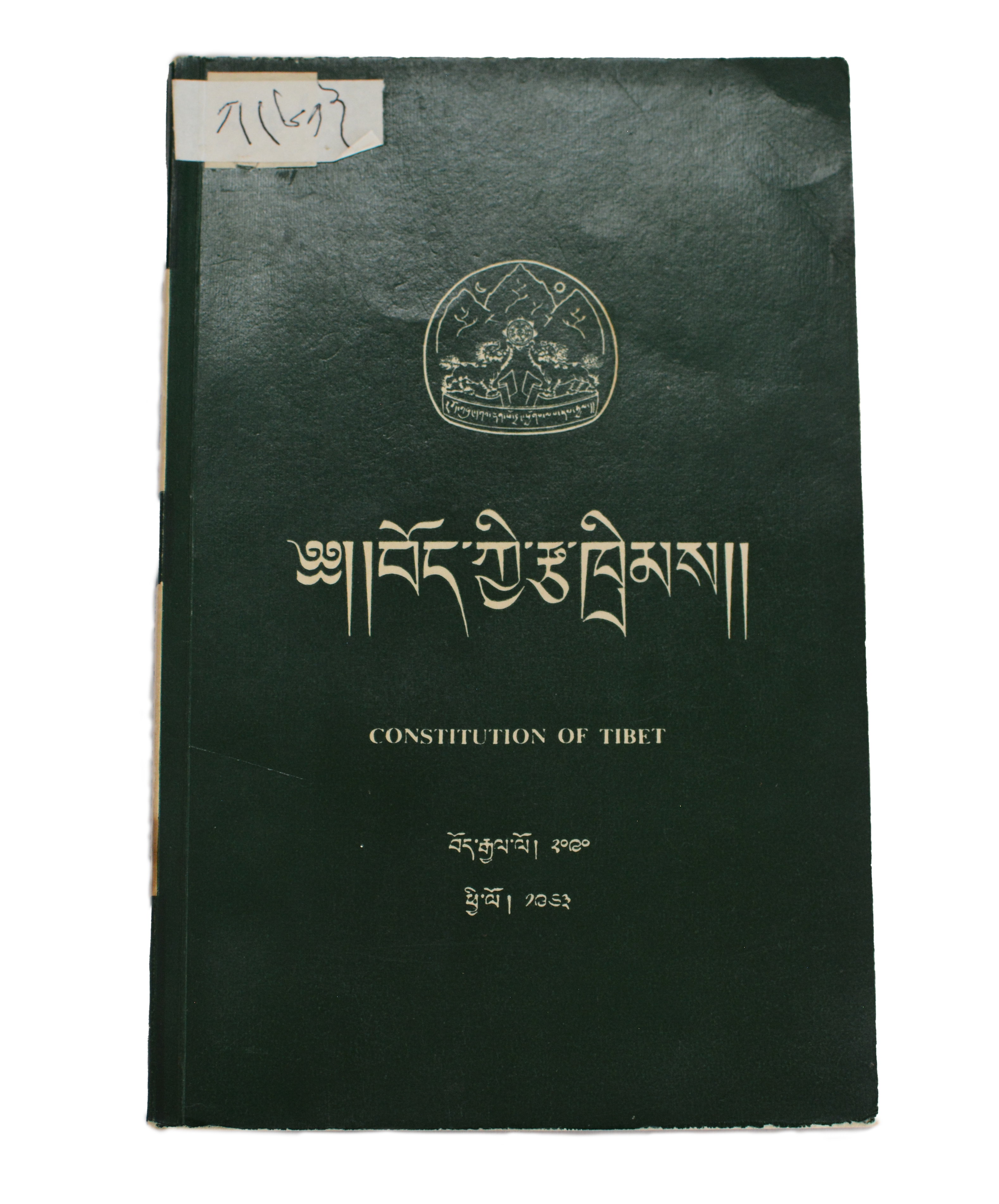

འདི་ནི་རྩ་ཁྲིམས་ཟིན་བྲིས་དེ་རེད། འདིའི་གཞི་རྩ་འགྲོ་བ་མིའི་ཐོབ་ཐང་ཡོངས་ཁྱབ་གསལ་སྒྲགས་དང་། ཡུལ་ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་གཞི་རྩའི་རྩ་འཛིན་ཁག་ལ་གཞི་བཅོལ་བ་ཞིག་ཡིན་རུང་། མཐའ་མའི་ཐག་གཅོད་བོད་མི་རྣམས་གཞིས་བྱེས་མཉམ་འཛོམས་ཀྱི་སྐབས་སུ་བྱ་རྒྱུ་རེད། ཡིག་ཆ་འདིར་༸གོང་ས་༸སྐྱབས་མགོན་ཆེན་པོའི་མ་འོངས་བོད་ཀྱི་མང་གཙོའི་དགོངས་གཞི་གསལ་ཞིང་། བཙན་བྱོལ་གྱི་གནས་སྐབས་འདི་ཉིད་མང་གཙོའི་ལམ་ལུགས་ཡར་རྒྱས་གཏོང་རྒྱུའི་གོ་སྐབས་དམ་འཛིན་གྱིས། རང་ཡུལ་བོད་ཕྱིར་ལོག་སྐབས་མང་གཙོའི་འགྲོ་ལུགས་ལག་བསྟར་ཐུབ་པ་དགོས་ཞེས་གསུང་གི་ཡོད།

This is a copy of the draft Constitution. It is based on the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Fundamental Principles of the Law of the Land. The ultimate decision as to whether or not the Constitution is adopted will rest with the Tibetan people when we are reunited in Tibet. This document records the Dalai Lama’s vision for a future democracy in Tibet. He believes this period of exile provides us with the chance to develop a democracy ready for when we return to Tibet.

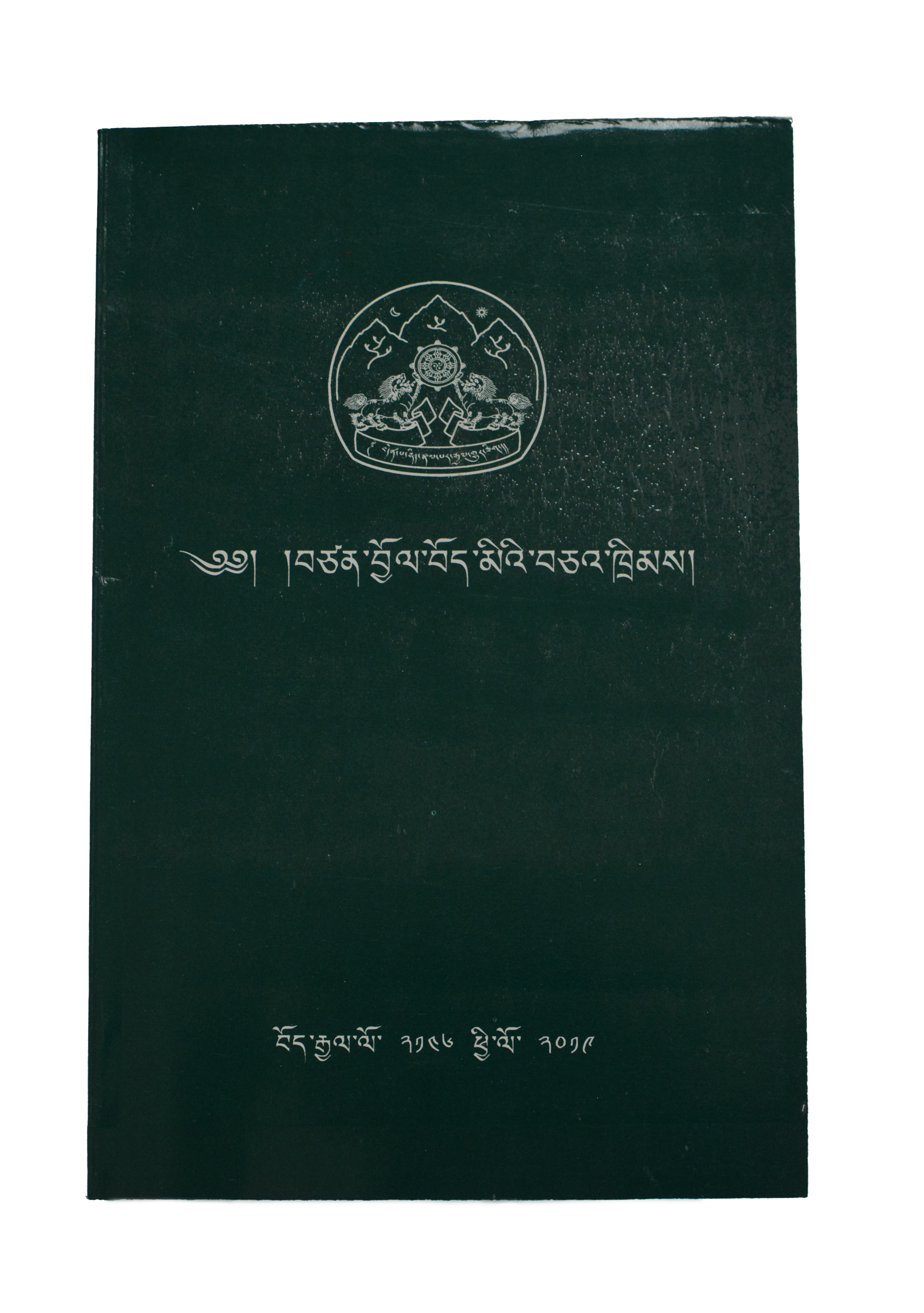

འདི་ནི་བཙན་བྱོལ་བོད་མིའི་བཅའ་ཁྲིམས་དེ་རེད། ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༡༩༩༡ ཟླ་བ་ ༦ པའི་ཚེས་ ༡༤ ཉིན་གཏན་ལ་ཕབ་པའི་བཅའ་ཁྲིམས་འདི་ཉིད་དབུས་བོད་མིའི་སྒྲིག་འཛུགས་འཛིན་སྐྱོང་གི་བླ་ན་མེད་པའི་ཁྲིམས་ལུགས་དེ་རེད། འདི་ཉིད་ཀྱི་གཞི་རྩར་ཡང་མཉམ་སྦྲེལ་རྒྱལ་ཚོགས་ཀྱི་འགྲོ་བ་མིའི་ཐོབ་ཐང་ཡོངས་ཁྱབ་གསལ་སྒྲགས་རྣམས་བཟུང་ཞིང་། ཁྲིམས་ཀྱི་མདུན་སར་ཕོ་མོ་དང་ཆོས་དད། རིགས་རུས། སྐད་ཡིག སྤྱི་ཚོགས་ཀྱི་འབྱུང་ཁུངས་ཇི་ཡིན་ལ་མ་ལྟོས་པར། བོད་མི་ཡོངས་རྫོགས་འདྲ་མཉམ་གྱི་འགན་ལེན་ཡོད་པ་གསལ་ཡོད།

This is a copy of the Charter of the Tibetans-in-Exile. The Charter, adopted on 14 June 1991, is the supreme law governing the functions of the CTA. It is based on the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It guarantees all Tibetans equality before the law and freedom without discrimination on the basis of sex, religion, race, language and social origin.

༸གོང་ས་༸སྐྱབས་མགོན་ཆེན་པོ་དང་མང་གཙོའི་ལམ་ལུགས།

༸གོང་ས་མཆོག་གིས་ཆབ་སྲིད་ཀྱི་སྐུ་དབང་རྩིས་སྤྲོད་གནང་སྟེ། མང་གཙོའི་དགོངས་བཞེད་མཐའ་སྐྱེལ་གནང་བ་རེད། ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༡༩༨༨ ལོར་བོད་མི་མང་སྤྱི་འཐུས་སྐབས་བཅུ་པར་མང་གཙོའི་བཅོས་སྒྱུར་ཆེ་ཙམ་གཏོང་རྒྱུའི་དགོངས་འཆར་གནང་བ་ནས། ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༢༠༡༡ ལོར་བཙན་བྱོལ་གཞུང་གི་ཆབ་སྲིད་དབུ་ཁྲིད་ཀྱི་སྐུ་དབང་དོར་ནས། མི་མང་གིས་འོས་འདེམས་བྱས་པའི་ཆབ་སྲིད་ཀྱི་དབུ་ཁྲིད་ལ་རྩིས་སྤྲོད་མ་གནང་བར་གྱི་ཐག་གཅོད་ཀྱི་གསུང་བཤད་ཟུར་འདོན་བྱས་པ་རྣམས་འདིར་གཟིགས་རྒྱུ་ཡོད།

The Dalai Lama and Democracy

The Dalai Lama has proved his commitment to democracy by downplaying his political role. From 1988, when the 10th Parliament-in-Exile was formed, the Dalai Lama pushed for greater democratic reforms. In 2011, the Dalai Lama stepped down from his role as political leader of the Government-in-Exile and an elected political leader replaced him. Here you can read the collected statements made by the Dalai Lama on his decision.

.png)